Medical Campus' Best Kept Secret: The Henry R. Winkler Center

Written by Chris Pasion, graduate assistant to The Graduate School.

Tucked in the basement of the Medical Campus’ sprawling Medical Sciences Building is an extensive archive that is over five hundred years in the making...

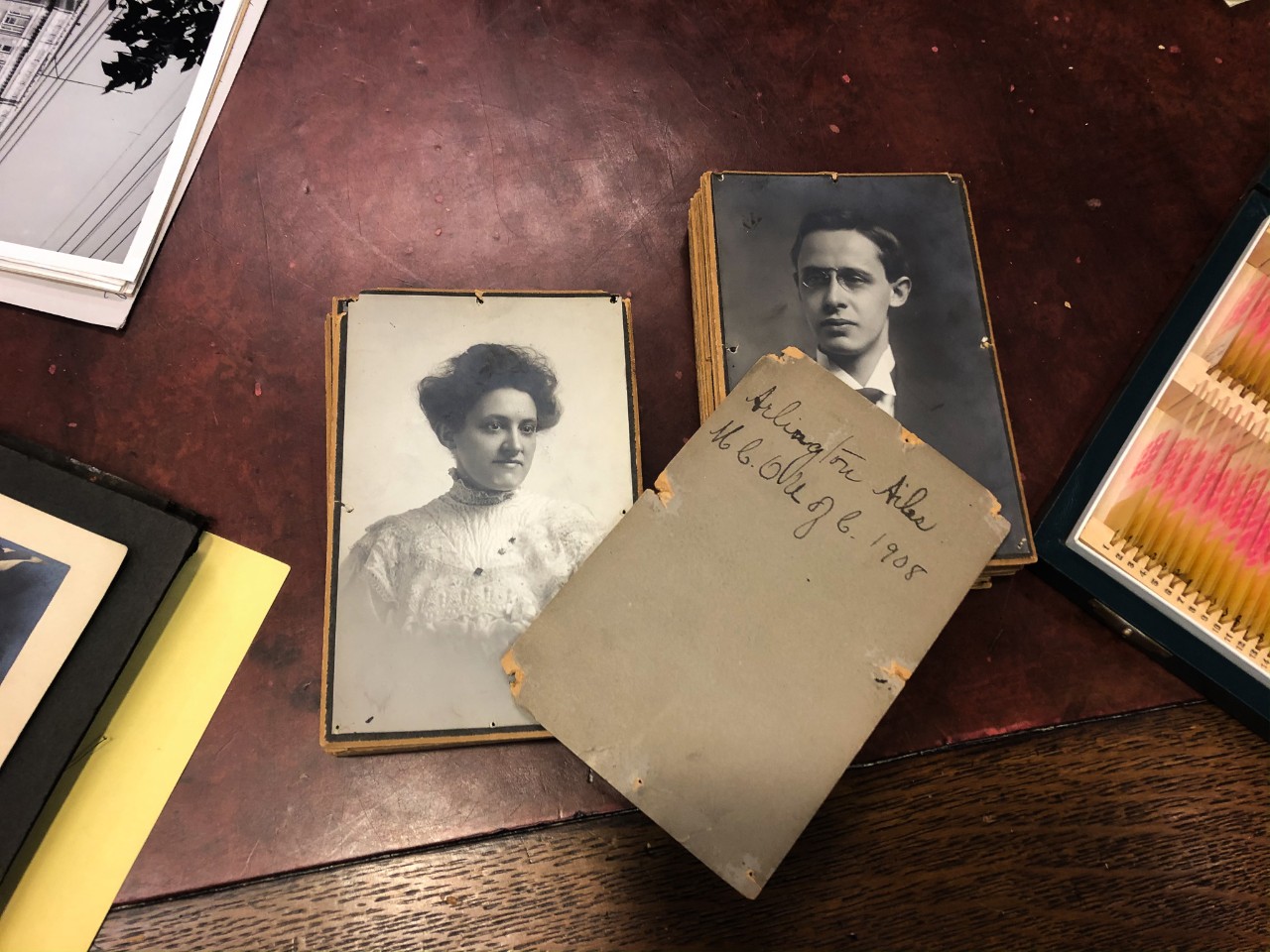

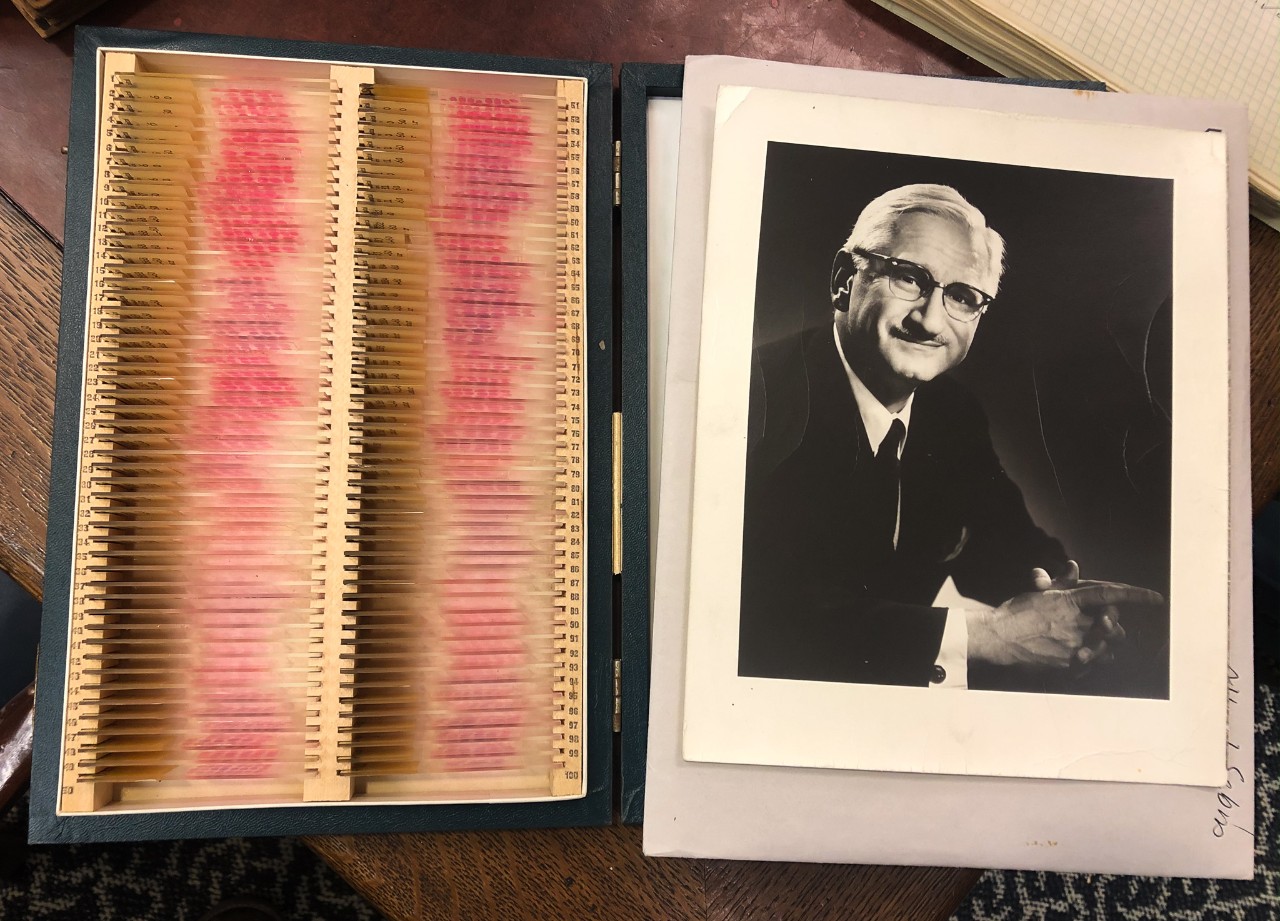

Albert Sabin's microscopic slides.

Behind a set of glass doors is the Henry R. Winkler Center for the History of Health Professions, an exhibit that showcases the medical history of the Cincinnati area and beyond. Many of those fun-facts that you may have learned on your campus tour, such as Albert Sabin’s development of the first oral polio vaccine or George Rieveschl's invention of Benadryl, originate here, tying Cincinnati to key medical discoveries that have allowed humanity to advance past formerly crippling diseases. The Winkler Center is a documentation of this and so much more.

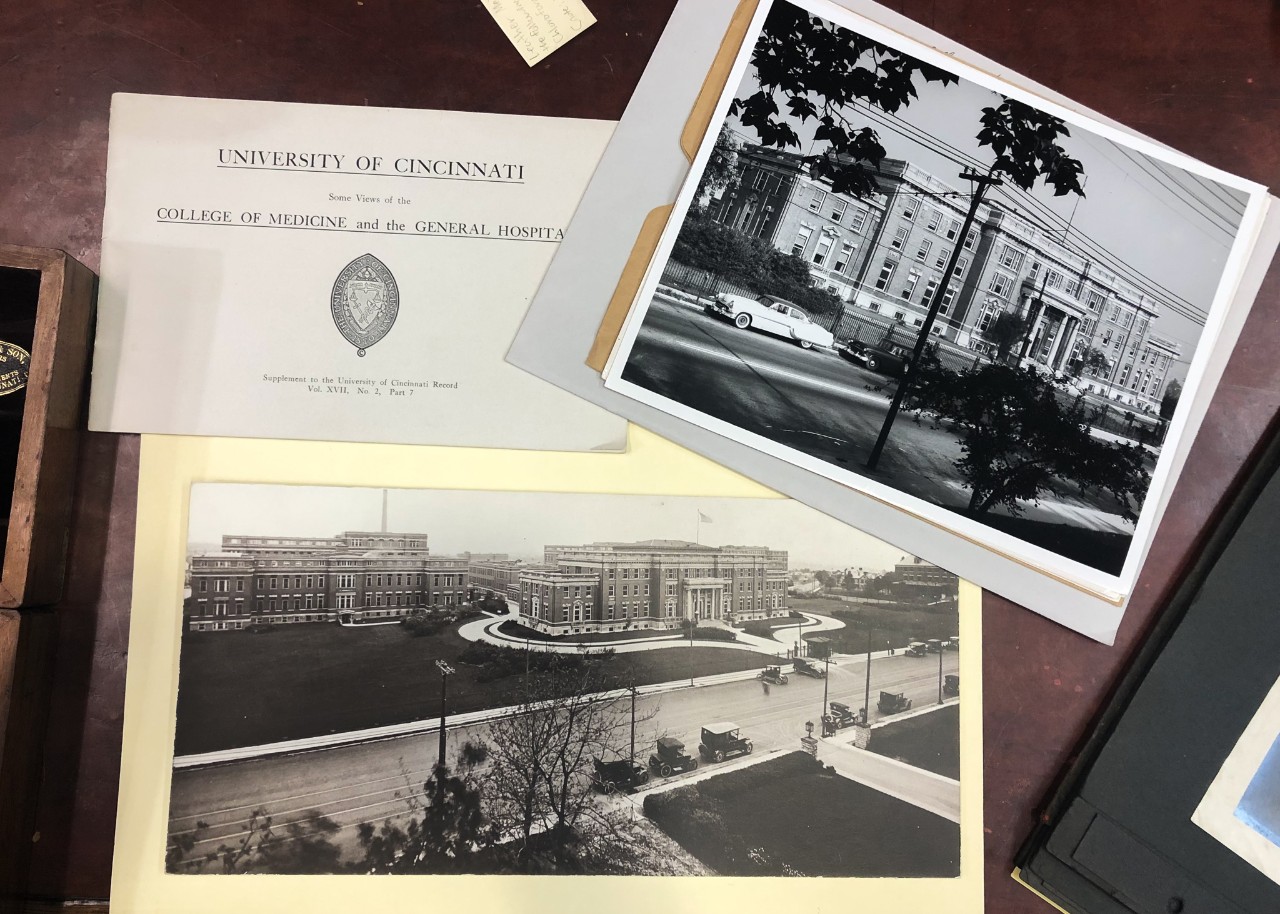

The Winkler Center began in the early 1970s as departmental libraries began to offload their collections from the previous 70-100 years. Rather than all of these materials go to waste in the landfill, they were housed in what would become the Winkler Center. Gino Pasi, the head archivist and curator, describes the inventory as being an eclectic collection of rare books on health sciences, archival materials from peoples’ personal collections, and instruments or objects related to health history.

An iron lung, a device used to assist people with respiratory failure.

Want an iron lung? They’ve got one on display. Looking for one-of-a-kind, surgical drawings from the battlefields of the Civil War, sketched with charcoal from memory by a surgeon after a long day of operating on the wounded? Gino would happily pull them for you to give a flip-through. Want to study a book that contains human lung tissue, cross-sectioned in a way that shows how it became ravaged from smoking, black lung, and asbestos? Well, that particular volume is currently at the UC Preservation Lab… The Winkler Center’s collection is as expansive as it is deep, and all of it is rife with opportunities for research.

Many of the people who conduct research in the Winkler Center are, contrary to what you might expect, not medical students; rather, the people who you might find researching at the Winkler Center are often from the humanities. Medical history is no longer a required class in many health-related curriculums, falling to the wayside as an elective that many are unable to fit into their busy and time-intensive schedules. “There are med-students here for five or six years who go their entire career here without knowing we exist,” Gino says. “They may sit right outside our doors for five years studying and never even think to come see us.”

A collection of medical quackery, such as the Electraply shock therapy device and a carton of asthmatic cigarettes, as well as Civil War surgical sketches, etc.

In addition to the serious, heavily researchable artifacts, the Winkler Center also has a small and interesting collection of what Gino refers to as “medical quackery.” In other words, pseudoscience. Items such as Dr. Guild’s Green Mountain asthmatic cigarettes, which promise to help alleviate asthmatic symptoms with each and every puff, or the Electraply shock therapy device, which delivers rejuvenating shocks pan-body, show an interesting, albeit misguided, side of history.

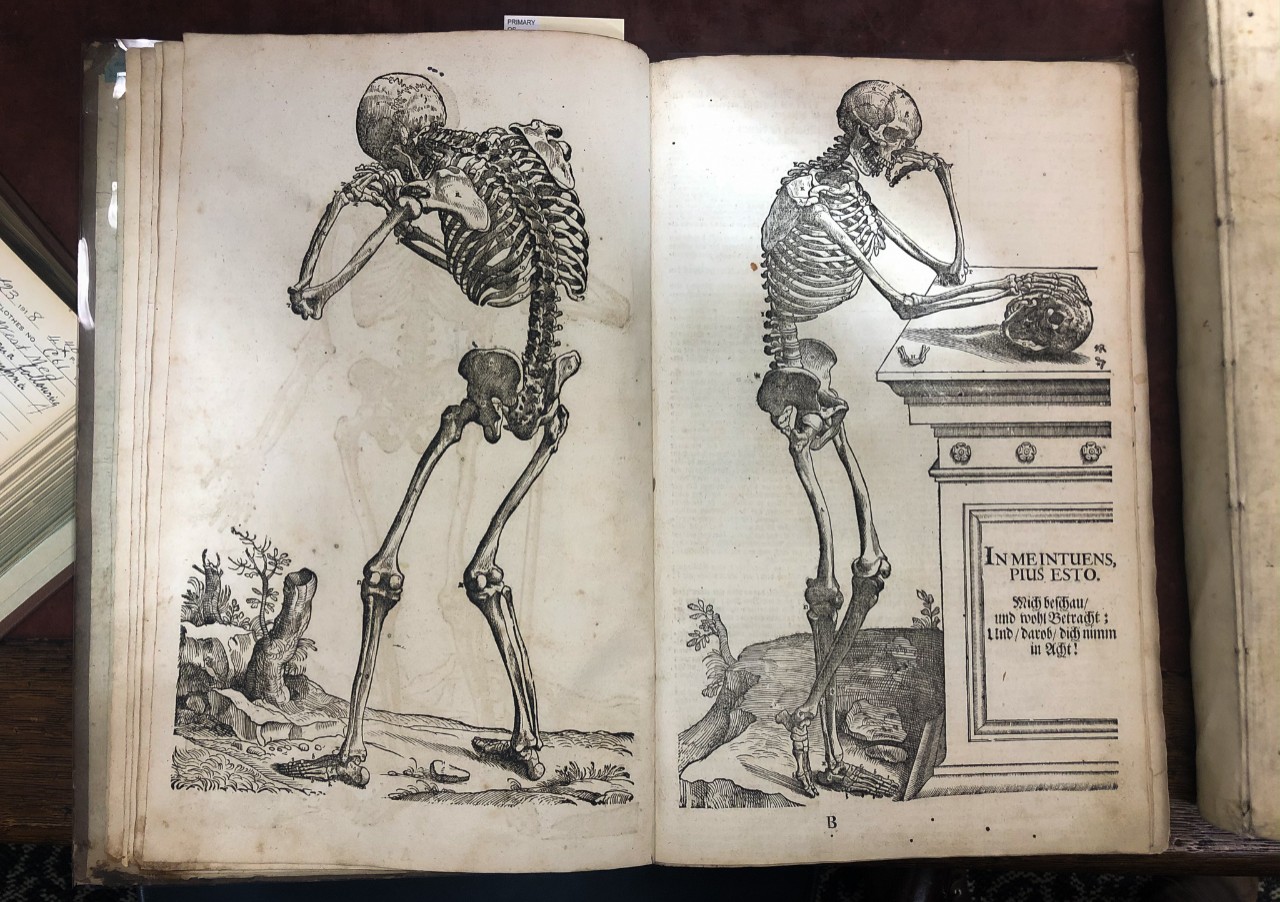

Other items in the collection, such as a wood-block-printed book on anatomy from legendary 16th century anatomist, Andreus Vesalius, show how medicine and art collide. The intricate drawings resemble Renaissance paintings, with skeletal figures populating elaborate scenes and posing in dramatic ways, many of which are accompanied by markings that delineate each and every bone and muscle in the human body.

16th century woodblock-printed anatomical diagrams by Andreas Vesalius.

Researchers at the Winkler Center range from high schoolers all the way up to doctoral students working on dissertations and beyond. Research is invaluable to our understanding of what these things mean and why they are important. Gino, who comes from an art background, describes how researchers have opened up his understanding of the medical world by saying, “When I look at these things, they often mean nothing to me. I got excited about these things when I discovered the history behind them.” Just by studying his microscopic slides, a researcher was able to pinpoint the exact moment that Sabin discovered the strain of polio virus which would end up in his vaccine. Sabin changed how polio was treated in that his vaccine could now be orally ingested, rather than with a needle and syringe. As Gino reflects on this discovery, he says, “When you discover that everything has a history and if you’re a historian or even the least bit intellectually curious, the more you know and the more you learn about things, the more passionate you become and the more you can talk about them.”

The Henry R. Winkler Center is a treasure trove of interesting things. Dive in and see what you can discover.

Browse the archives, request items to research, or book a visit on the Winkler Center’s website.